Art and Fashion

Watercolour in Victorian times

Watercolour is a type of pigment that is dissolved in water. It is commonly applied using a brush onto dampened paper to create art. Watercolour artwork grew in popularity as the materials became more commercially available. The “shilling colour box” was a popular item for amateur artists. It was a pocket-sized tin container with watercolour pigments in small cakes with removable tin water vessels. More than 11 million units were sold from 1853 to 1870.

Both Victorian men and women created art, but women were often limited to “feminine” genres of small-scale landscapes, still-life, or family portraits. However, some female painters defied convention and founded painting societies, such as the Society of Women Artists, to advocate for their profession. Laura Herford was the first woman accepted into the Royal Academy of Arts in 1860. The Slade foundation (est. 1871) notably offered equal education for men and women in the arts.

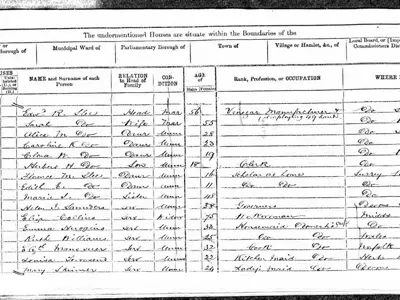

From ca. 1869-1873, several women of the Slee family painted watercolour artworks of female subjects. Some of the artworks are signed with “SF” and “CW.” “CW” is likely Clara Westwood Farquhar (née Slee) (1851-1925), who was 18 years old in 1869. “SF” could be Sarah Slee, who was 53 years old in 1869, but no middle name is reported in her records. “SF” could also be Florence Mary Slee (1854-1940), who was 15 years old in 1869. These women could have been artistically trained, but it is likely they were amateur artists.

Fashion Trends

To the Slee family and other upper class women, fashion was more than self-expression – it signified social status and respectability. An 1865 issue of Beeton's housewife's treasury of domestic information wrote that:

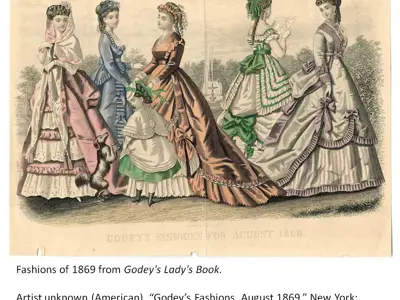

In the nineteenth-century, fashion was constantly changing amidst new inventions and styles. In the early 1860s, dresses were wide and bell-shaped. In the mid-1860s, skirts became flatter in the front with more fullness on the back. This new shape was supported by the crinoline and the bustle or “dress improver” which helped to drape fabric into the appropriate style. Hair became styled higher than in the early 1860s to accommodate the taller bustles. Many women also used false hair pieces to add volume to braids and curls.

Corsets were commonly worn to shape the waist and became stiffened with materials such as whalebone. The Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) highlights that “ordinary people probably adapted the tightness of their corsets for the occasion,” dispelling the notion that corsets were disease-inducing devices.

The first artificial dye was invented in 1856 by Sir William Henry Perkin. It was a bright purple known as “aniline violet” or “mauveine.” Women’s dresses became dyed with bright colours, which caused etiquette experts to advise that only two to three colours be used per outfit. The outfits in the Slee watercolour paintings reflect the new shapes and colourful attire of the late 1860s.

Contact Us

Community Archives

254 Pinnacle Street

Belleville, Ontario

K8N 3B1

phone: 613-967-3304

email: archives@cabhc.ca